‘The way today’s youth run the world’

By Amy Kulikowski

HAMDEN, Conn. — Norman Zercher’s mother shouted from upstairs, “Shut that off and turn the radio on!” “Why?” Asked Zercher, then 6-years-old. “Is Santa Claus on?”

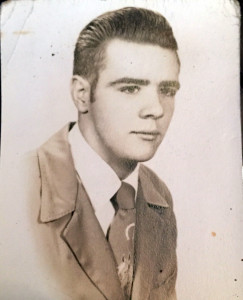

Norman Zercher, 80, of New London

His mother said no, but to turn the jukebox off anyway and listen to the radio. Zercher, now 80-years-old, did so and listened to the announcers talking about an attack on Pearl Harbor.

“I thought at first that it was a girl,” said Zercher. “I didn’t know who, or what, Pearl Harbor was.”

He went to school the next day to find out about Pearl Harbor. He related the attack to 9/11, and how kids know what that date means today.

“To us, December of 1941 was just as important,” said Zercher.

At age 6, Zercher’s father was still alive, but when he was 10-years-old, his father died. He said he never really got to know him, and that he detested his step-father.

However, Zercher said he behaved no matter what. He respected his elders, but today he sees a lack of respect in children to their parents.

“The biggest change that I’ve seen, and I really have not gotten used to it yet, is the way today’s youth runs the world, tells their parents where to go and so forth,” said Zercher. “Just total lack of respect.”

When Zercher was a child living in Wayne, Pa., he said he either behaved or he got a whipping–although, today, you’re not allowed to touch a child.

According to the Connecticut Law about Child Abuse and Neglect from the Connecticut Judicial Branch, if a child is believed to be neglected and endured physical harm, a law enforcement officer is authorized to remove the child from the situation without permission from a parent or guardian.

While the child is in a 96-hour hold, the commissioner provides medical care, which includes an examination of the child without any permission. The physician then decides if there is any abuse, which is defined as physical injury without accidental means or maltreatment, or neglect, which is defined as abandonment, being denied proper care or being allowed to live under harmful conditions.

Zercher remembered about five years after he was married and moved away, he was home one day and made some kind of sarcastic remark to his mother.

“My mother looked at me and said, you’re not old enough or big enough yet that I can’t knock you down, and she meant it!” said Zercher, laughing.

When World War II was declared, Zercher said he soon learned about war.

He said everyone went on rationing, the controlled distribution of scarce resources or goods of demand, and they had stamps for just about everything.

“If you went to the store to buy meat, you had to have so many A stamps, or so many B stamps to buy this quantity of meat, or this quality of certain restricted items,” said Zercher.

Gasoline was also rationed. Because Zercher’s father was in business, he said he was “pulling his hair out” because he couldn’t get gas for his vehicles to do his work.

“The war meant that people were fighting somewhere, and because they were fighting, we were sending everything to them and we had nothing to ourselves because of it,” said Zercher. “We were taught this was the patriotic thing to do, and we lived with it; we did it.”

He remembered blackouts and when the air raid wardens would come around at night after the siren blew. Zercher said that if they could detect the least bit of light in the house, they would yell in the window “shut the lights off!”

“In school, we had to learn how to get under the desk real quick when we heard the sirens blow, because that was supposed to be bomb proof,” said Zercher.

Zercher graduated from high school in 1953, learned the machinist trade, and starting working for a few months after he graduated in the trade.

“Looking out the window and seeing people go by, walking, driving, not being stuck in a shop, I realized this is not for me,” said Zercher.

Accidently, Zercher said that a friend of his was looking for someone on a temporary basis in the pest control business. Zercher was in it for 62 years, until he retired last year.

“I didn’t want to retire, but when I turned 80, my company said to me, you’re done,” he said laughing. “I’m still not happy about the whole thing.”

Currently, Zercher is not working. He said he is looking for a small job, so he has a few hours a day to do something.

“Sitting around watching television is not my idea of a fun day,” said Zercher.

He went into the service when we was 22. He married his first wife prior, so that she could go with him anywhere he went.

“We went from Philadelphia to New London, Conn., and that’s as far as I went,” said Zercher.

He was in the Navy Reserves and became a Petty officer and assigned to a dry dock in Groton, which meant it was welded to the pier and he didn’t go anywhere.

While he was still in the Navy, he was working part-time in a summer restaurant in Niantic, waiting on tables. When Zercher told his customers the restaurant was closing for the winter, one customer asked him how he would like to get into pest control.

“I was in pest control before I joined the Navy, why not stay in it,” Zercher told the customer.

Together, they made his business into one of the biggest ones in the New London area, called Eastern Chemical Service. Zercher worked for various companies over the years, including the owners of Campbell’s Soup.

He said the funniest celebrity he ever met, was a woman who illustrated a book called “Silent Spring.”

“It was a story about how pesticides are going to wreck the world and we’re going to come to a screeching halt, because everybody is using pesticides,” said Zercher.

The illustrator and her husband were naturalists, and Zercher’s first wife got to know her through working at the Mystic Seaport. She asked his wife about him and said she wanted to see Zercher.

Zercher said he walked into the house and she said to him, “Look what those termites have done to my house!”

“After the woman showed me all of the damage they had created, she said to me, I don’t care what pesticides you use, get rid of them,” said Zercher, smiling.

Zercher and his first wife and he were high school sweethearts, but she died when she was only 51.

“I was never going to get married again, then I met this gal,” said Zercher, referring to his current wife, Ellie.

They have been together for 27 years. Zercher said that her family loves him, and his family loves her, and is just something that worked out perfectly.

“I never thought I would ever be that happy again,” said Zercher, joy spreading across his face.

As Zercher reflected on the biggest change, he would also describe it as how morals are different.

“Business is done a lot different than how it was done years ago, but you still get the job done, making money and earning a living,” said Zercher.

The change has been so gradual in his lifetime, almost like a metamorphosis.