‘We didn’t have telephones yet’

By Taylor Nicole Richards

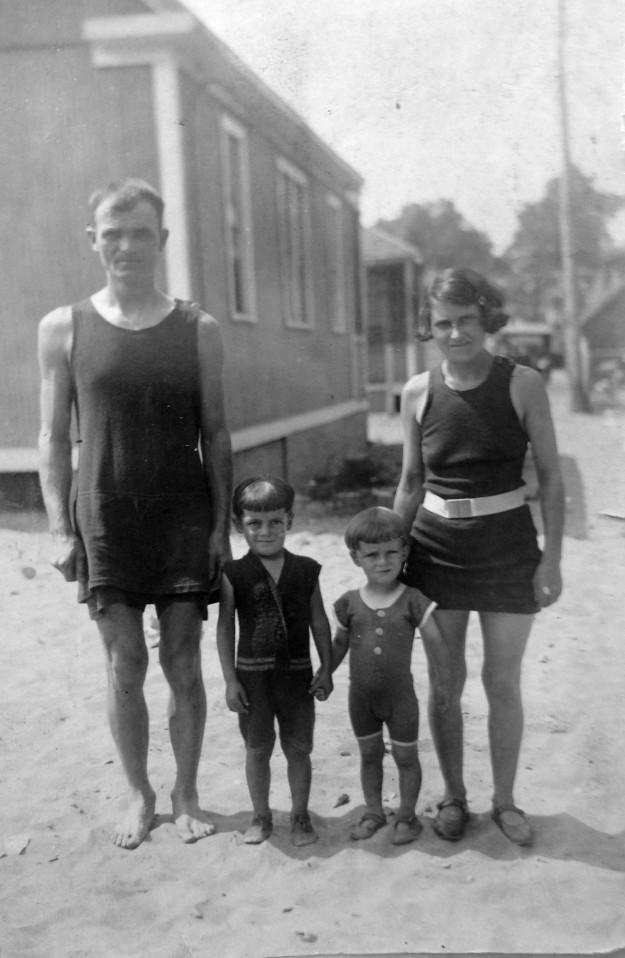

When Ludwig “Lud” Coiro grew up in the 1920s and ‘30s, everything was quieter. No lawnmowers, snowblowers, or loud cars to fill the air in the south end of Hartford. There were acres of open fields, and when Coiro’s neighbor a few blocks over turned on her vacuum cleaner, he could hear it from his house.

Noise and light pollution is what Coiro said is the biggest change he’s witnessed in his lifetime. Even though Coiro said pollution was the greatest change, his recollections showed the change in the way Americans communicate with each other impacted him the most.

“When I was a teenager, we didn’t have telephones yet,” said Coiro. “I used to deliver telegrams for the Western Union by bicycle at nights and on weekends.”

The advancement of technology and how it affected communication played an important role throughout Coiro’s life.

“My grandmother had an old pedestal-style telephone. Me and my brother would sneak over to pick it up and the lady would say ‘number please’ and we’d giggle and hang up,” he said.

According to Coiro, Hartford got televisions for the first time in 1948. He immediately picked up a 10-inch set for $400. He also remembered when computers were first introduced at Pratt and Whitney in Hartford. Coiro worked for 40 years as an engineer designing aircrafts, engines, rockets, and fuel cells without a college degree. He said designs he worked on decades ago are still on display at the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks.

“I used to do all my calculations on a slide rule. The first handheld computers came out for $250, now they’re around $10. I was amazed that I could just push a button and get a square root,” said Coiro. “I think technology is a great thing if you use it correctly.”

Now, he has his own computer that he goes on frequently to surf the web. Coiro taught himself how to use a PC when he was around 80-years-old and has been using one ever since. He often sends emails to family members and browses the internet to learn new things.

From delivering telegrams to sending emails, Coiro has followed technology’s ever-expanding resources to communicate his entire life. He joked that now he should carry around a dummy cell phone just so he can at least look up-to-date, since he’s been following technology his whole life.

Communication through technology was a profound change for Coiro, but there was also a shift in general spoken communication in his lifetime. He insisted that people treated each other differently now than when he was younger.

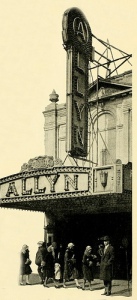

“Me and my brother worked at the Allyn theater uptown in Hartford when I was 19. We used to walk from there to the south end and we weren’t afraid of anything,” said Coiro. “There was nothing to be afraid of. No one used to lock their doors. No one locked their cars either. Nobody would ever think of going near somebody’s car; that was somebody’s car.”

During the time of Coiro’s adolescence, the index crime rate was under 1,000 reported crimes for per 100,000 people, according to historical data from the Justice Research and Statistics Association. Crimes documented in the study included murder, rape, aggravated assault, grand theft auto, burglary, and larceny.

Coiro said that it used to be a big deal to go uptown in Hartford. There were many nice stores and everyone would dress up. He would go out with his girlfriend Julie. She would never be bothered or catcalled because he thinks that women were respected more during that time. He’s not sure why it’s so different now, but he knows that television played its part in “spoiling” the way women were presented.

The change in the way Americans treat one another around the entire country, not just in Connecticut, has definitely shifted in Coiro’s opinion. A few years after he got his job at Pratt and Whitney, he joined the air force in World War II. What he saw fighting in the Pacific is too emotional for Coiro to speak about it. However, he has many fond memories of travelling from base to base across the country with his wife Julie before leaving for war. He said that people were very hospitable and respectful to the servicemen.

“As we travelled, we would stop in little towns and they would always treat us nice. I remember once we went to a little restaurant and we didn’t have much money. We’d order small and bring in our own can of spam while our dog sat at our feet. The owner of the restaurant came over with a plate of ham and beans to give to the dog. You just don’t see that now.”

Another instance of general hospitality Coiro experienced was when he and his wife’s car broke down during their travels around the country. A man nearby parked it at his house and fixed the issue, but found a new problem with the radiator. For all the work he did, he only charged Coiro for the price of the new radiator. As the couple was about to leave, they realized that his battery completely died. The same man bought and installed a new battery. Coiro didn’t have enough money to pay him, so the man gave him his address and told Coiro to send him the money whenever he was able to. Once he was back in Connecticut, he went back to work and was able to send the man the money.

Even though Coiro has trouble looking back on his past in the military, he appreciated the overall kind nature and respected opinion Americans had toward the men fighting the war. This made Coiro proud of his time in service.

There have been great physical changes to America over the course of Coiro’s lifetime. The changes that he felt the strongest were the ones that related to the way Americans communicate and treat each other, whether it was influenced by advancements in technology or stress in time of war and conflict. Coiro looks back longingly on a time when there were quieter streets, fewer advertisements, slower weekends, and friendlier citizens. Even though he remembers and appreciated the simplicity of time passed, Coiro said he is content with the way he lives his life now and just wants people to remember him for “being a nice guy.”